Season 2019

So here we are as supporters in a summer of discontent. Nothing can escape the reality that a premiership defence resulted in a sixth-place finish, with three of the last four matches being losses.

With a slim advantage and the season on the line, a limp final quarter of a singular point in the face of four Geelong goals sealed the club’s elimination at the second hurdle of the post-season.

It was a performance that summarised the season – a poor start, followed by a fightback into ascendancy, only to suffer a disappointing capitulation at the finish.

What started as an aberration in the Queensland humidity quickly became a hangover as after just six matches the club had already suffered three defeats by larger margins than during the entirety of 2018. Despite winning 12 of the next 14, things still seemed “off” – opponents were rarely put to the sword and easy goals were leaked which kept them in the contest. After being a team that could never be counted out in 2018, there was an increasing uncertainty over its ability to run out games. Aside from front-running in perfect weather conditions, the impression was of fragility that could break against stronger opposition.

And with that a change in the weather on a Sunday afternoon late in winter changed the outcome of the season.

A four goal lead under the sun became a six point loss in a downpour against Richmond in arguably the match of the season, costing the chance of a top two finish. Six days later the club was still struggling to recover its condition after that slog when it hosted Hawthorn. The Hawks were conversely in top condition after facing barely training-level intensity the week prior against Gold Coast in the Jarryd Roughead testimonial match – the situation was primed for an upset. Outscored by 13 goals to 5 after quarter time, the loss in the final game of the regular season denied the club a place inside the top four and any realistic chance of defending the premiership.

If that Round 22 clash against the Tigers had occurred on the Saturday, or commenced an hour earlier, would we be looking at a different outcome? Perhaps. The likelihood of a top two finish and fine conditions throughout September point towards another Grand Final appearance. At the same time, Richmond would be entering finals from outside the top four. The magnitude of lost opportunity only increases the more you think about it.

Speculation such as this is disingenuous, however. To be successful, teams obviously need to play well in all conditions, against differing tactical approaches. In 2019 West Coast was, for a number of reasons, unable to do this.

Was 2019 an underachievement? In terms of the quality available, it can only be an overwhelming YES. Never has the club been presented with better circumstances of winning consecutive premierships. Without question more should have been achieved from a squad that was near to full-strength at the end of the season. Chances were not readily taken however and match situations that eventuated as victories in 2018 dwindled into losses.

The 2019 season will be recalled as one of the greatest disappointments and missed opportunities in the history of the club.

What went wrong?

The decline of the Eagles in their 2019 premiership defence can be traced to two major reasons:

The Gameplan

Winning the premiership places a team under intense scrutiny unlike anything else. Suddenly there are 17 other teams who are marking their calendars for an opportunity to take you down – each of them pouring over hours upon hours of footage looking for a weakness that can be exploited. There are no matches in isolation for the premiers – if you stumble, everyone else is watching, studying and learning from it.

So it was for the Eagles in 2019.

As detailed previously here, the static positioning of the defence allowed opponents to push non-key forwards up the ground, creating additional turnover pressure post-stoppage and avenues through which rapid counterattacks could be launched.

The band aid response from the team was to move its own non-key half forwards to a more defensive mindset, spending considerably more time up the ground in the defensive half. This served to stem the ease of opposition scoring, but restricted the options for offensive ball movement and further hampered the team’s ability to win contested situations outside of stoppages.

Thus a team that had seven players averaging over 8 contested possessions per game was also ranked last in the competition for contested possessions overall.

The majority of the team are not impacting upon contested situations.

The aforementioned effect on attacking ball use made the team far more predictable in its movement and opponents set themselves up to ensure that no one-on-one marking contests occurred from the expected kick down the wing to a tall target. Furthermore, this predictability led to an increasing number of opponents fielding Richmond-style counterattacking setups through the midfield corridor in anticipation of the spoil from this contest.

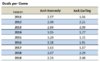

This is reflected in the changes seen in contested marks and turnovers in 2019 compared to 2018:

Average numbers for contested marks have gone down whilst turnovers have gone up.

The most damaging development from a tactical perspective however was the negation of the aerobic sweeper role that had played such an important part in 2018’s success. Indeed, by the close of the season this had become so complete that the role itself had become a liability.

With non-key position forwards curtailing their numbers of aggressive leads ahead of the ball, the onus is increasingly upon the tall forwards as targets in attack – but the predictable ball movement ends up making them play right into the hands of the opposition. Man up the target (usually ruck or third tall) in the corridor and it guarantees that the kick going forward from the defensive half will be towards the key forward that is leading up to the wing. Opponents are also well aware that this no longer represents a dangerous position; even if the ball is marked, if the smalls are not getting into clear space and presenting a short option then the only means left to go forward is to bomb it long in the direction of the remaining key forward. So what does the opposition do? Let the key forward roam up the ground, using the ruckman to check against his marking contests – allowing his defensive counterpart to stay at home as a marking spare. Thus, the ball can be marked, spoiled, roved, whatever – the only way it is getting forward is through a long, high kick to an outnumbered marking contest. It is from this situation that the rot begins.

The kick comes in; it’s a one-vs-two. The forward gets front position but is restrained by his marker just enough to not give away a free kick but allow his teammate to come across as a spare in front and take the intercept mark. The defence then quickly utilises its superior numbers to launch a counterattacking possession chain through the corridor. It is the template that this team introduced to the competition in 2015 – safe to say that it is disappointing to watch the team now be ravaged by it four years later. It gets worse however; in this situation the aerobic sweeper role from the 2018 gameplan actually makes it easier for opposition counteroffensives to break through the defensive zone and concede “cheap” goals.

The defence of the Eagles is a fine-tuned machine. It is able to comprehensively shut down opposition attacks and yet still be aggressively counteroffensive when the game is being played on its terms. That last part is the key piece – when the game is being played on its terms – because increasingly so during matches, that is no longer the case and the consequence is a major factor in the undoing of the defence of the premiership.

Imagine a box stretching from the centre of the ground to 40m from defensive goal one way and the width of the corridor between the wings on the other – that is the no mark zone of the West Coast defence. The entire setup of the defence as a team and its approach is geared towards preventing opposition marks from taking place in this dangerous area and forcing turnovers from intercept marks. To that end it requires the opposition to be forced into rushed decisions to get the ball forward under pressure. Additionally, the aerobic sweeper role adapted from the wing covered the lead-up space ahead of opposition targets in the corridor, ensuring that any attacking kicks coming in would be high and thus to the advantage of the Eagles’ superior marking backmen.

With the intercept mark taken in the corridor, options for counterattack were then readily available to the left, right and centre. That is the foundation behind the success of 2018.

But what happens if the intercept mark is not taken? Indeed what happens if the incoming kick bypasses the defensive trap for intercept marking entirely? That fine-tuned defensive machine becomes very vulnerable outside of its comfort zone.

So now we have an opposition possession chain counterattacking from defence with the aid of numerical supremacy from spares stationed deep behind the ball. The opposition also know to avoid that first option long kick against the Eagles in order to avoid McGovern, Barrass, Hurn, Sheppard etc. Instead they look to handball and run rather than kick. Remember 2006? The way to beat the flood was run and receive – “happy handball” as it was termed at the time. The same can be said of zones; use running chains to pull it out of shape, allowing a position where it can then be rendered useless by kicking over it. Think of it like basketball and the deployment of a compact zone being undone through the execution of play via the high-post.

When the long kick does not come, it places the entire defence on its heels. McGovern and Barrass have already pushed up and assumed the space ahead of their opponent in preparation to intercept – with the kick not coming, they are now scrambling to get back on their marks with the disadvantage of running towards goal and limited view of where the ball is. The aerobic sweeper continues to cover the lead-up space ahead of targets in the corridor, but all that does now is provide additional space for the opposition to continue the possession chain and progress into a dangerous attacking area forward of centre. When the kick does come it is deep and beyond where the defensive zone was set. In the resulting confusion to cover tall forwards, opposing non-key forwards are often able to find space behind the defence and get easy goals. All the while half the crowd boos whilst the other half are screaming out “How the %#@& did that happen?!”.

Negation of the aerobic sweeper role:

1. Aerobic sweeper is set in position covering opposition forward lead-up space.

2. Opposition creates short possession chain out of defence;

3. Instead the kick comes in long and bypasses the zone. Defenders are left scrambling whilst opposition forwards get behind them and gain easy goals.

With the aerobic sweeper role a liability, Masten, who had specialised himself within it to the point that he was unable to hold down any other role, was made redundant. That he was subsequently delisted at the end of the season may or may not be coincidental.

It leaves one of the catalysts behind the tactical triumph of 2018 on the scrap heap with a question mark hanging over what will be adapted as its replacement.

The Talls

The club has at its disposal the best collection of key position players in the competition. With that array of riches however comes the temptation to play too many of them, upsetting the balance of the team.

Those who are familiar with my musings will know that this is a particular theme that I have raised on numerous occasions previously, most recently at length here.

Later in this piece it shall be discussed that the biggest tactical development in the competition over the past two seasons has been the emphasis upon rebounding and attacking from defence. Such tactics favour players with pace and overlap running ability, typically not characteristics of key-position types. Turning that around, the conclusion is the more key talls that are fielded on the ground, the greater the disadvantage against the overall trend of the competition.

In 2019 this conclusion proved true for the club, especially so up forward.

Starting with four tall forwards and two rucks in Round 1 against Brisbane, throughout the season a preference for marking advantage in attack drove the selection of the team for a negative return:

Average score differential across quarters for numbers of KPP used up forward.

Fewer numbers correlate with both greater scoring overall and in the later periods of matches.

2018 demonstrated without question that two specialist key forwards in addition to a resting ruck/forward was a platform for success – namely premiership success. It has also had the most success this season out of varying forward arrangements.

It remains to be answered why on earth anybody would deviate from it, when it is by far the best option available?

Combined, these factors resulted in the team having the following shortcomings in season 2019:

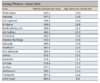

The statistics in these areas are pretty damning:

There is work that needs to be done before the club can lift up the Cup again in September.

So here we are as supporters in a summer of discontent. Nothing can escape the reality that a premiership defence resulted in a sixth-place finish, with three of the last four matches being losses.

With a slim advantage and the season on the line, a limp final quarter of a singular point in the face of four Geelong goals sealed the club’s elimination at the second hurdle of the post-season.

It was a performance that summarised the season – a poor start, followed by a fightback into ascendancy, only to suffer a disappointing capitulation at the finish.

What started as an aberration in the Queensland humidity quickly became a hangover as after just six matches the club had already suffered three defeats by larger margins than during the entirety of 2018. Despite winning 12 of the next 14, things still seemed “off” – opponents were rarely put to the sword and easy goals were leaked which kept them in the contest. After being a team that could never be counted out in 2018, there was an increasing uncertainty over its ability to run out games. Aside from front-running in perfect weather conditions, the impression was of fragility that could break against stronger opposition.

And with that a change in the weather on a Sunday afternoon late in winter changed the outcome of the season.

A four goal lead under the sun became a six point loss in a downpour against Richmond in arguably the match of the season, costing the chance of a top two finish. Six days later the club was still struggling to recover its condition after that slog when it hosted Hawthorn. The Hawks were conversely in top condition after facing barely training-level intensity the week prior against Gold Coast in the Jarryd Roughead testimonial match – the situation was primed for an upset. Outscored by 13 goals to 5 after quarter time, the loss in the final game of the regular season denied the club a place inside the top four and any realistic chance of defending the premiership.

If that Round 22 clash against the Tigers had occurred on the Saturday, or commenced an hour earlier, would we be looking at a different outcome? Perhaps. The likelihood of a top two finish and fine conditions throughout September point towards another Grand Final appearance. At the same time, Richmond would be entering finals from outside the top four. The magnitude of lost opportunity only increases the more you think about it.

Speculation such as this is disingenuous, however. To be successful, teams obviously need to play well in all conditions, against differing tactical approaches. In 2019 West Coast was, for a number of reasons, unable to do this.

Was 2019 an underachievement? In terms of the quality available, it can only be an overwhelming YES. Never has the club been presented with better circumstances of winning consecutive premierships. Without question more should have been achieved from a squad that was near to full-strength at the end of the season. Chances were not readily taken however and match situations that eventuated as victories in 2018 dwindled into losses.

The 2019 season will be recalled as one of the greatest disappointments and missed opportunities in the history of the club.

What went wrong?

The decline of the Eagles in their 2019 premiership defence can be traced to two major reasons:

- The competition adapted and responded to the control-orientated gameplan that proved so successful in 2018.

- The club had an unhealthy preference for selecting an overabundance of key talls (particularly up forward), which caused problems elsewhere throughout the team.

The Gameplan

Winning the premiership places a team under intense scrutiny unlike anything else. Suddenly there are 17 other teams who are marking their calendars for an opportunity to take you down – each of them pouring over hours upon hours of footage looking for a weakness that can be exploited. There are no matches in isolation for the premiers – if you stumble, everyone else is watching, studying and learning from it.

So it was for the Eagles in 2019.

As detailed previously here, the static positioning of the defence allowed opponents to push non-key forwards up the ground, creating additional turnover pressure post-stoppage and avenues through which rapid counterattacks could be launched.

The band aid response from the team was to move its own non-key half forwards to a more defensive mindset, spending considerably more time up the ground in the defensive half. This served to stem the ease of opposition scoring, but restricted the options for offensive ball movement and further hampered the team’s ability to win contested situations outside of stoppages.

Thus a team that had seven players averaging over 8 contested possessions per game was also ranked last in the competition for contested possessions overall.

The majority of the team are not impacting upon contested situations.

The aforementioned effect on attacking ball use made the team far more predictable in its movement and opponents set themselves up to ensure that no one-on-one marking contests occurred from the expected kick down the wing to a tall target. Furthermore, this predictability led to an increasing number of opponents fielding Richmond-style counterattacking setups through the midfield corridor in anticipation of the spoil from this contest.

This is reflected in the changes seen in contested marks and turnovers in 2019 compared to 2018:

Average numbers for contested marks have gone down whilst turnovers have gone up.

The most damaging development from a tactical perspective however was the negation of the aerobic sweeper role that had played such an important part in 2018’s success. Indeed, by the close of the season this had become so complete that the role itself had become a liability.

With non-key position forwards curtailing their numbers of aggressive leads ahead of the ball, the onus is increasingly upon the tall forwards as targets in attack – but the predictable ball movement ends up making them play right into the hands of the opposition. Man up the target (usually ruck or third tall) in the corridor and it guarantees that the kick going forward from the defensive half will be towards the key forward that is leading up to the wing. Opponents are also well aware that this no longer represents a dangerous position; even if the ball is marked, if the smalls are not getting into clear space and presenting a short option then the only means left to go forward is to bomb it long in the direction of the remaining key forward. So what does the opposition do? Let the key forward roam up the ground, using the ruckman to check against his marking contests – allowing his defensive counterpart to stay at home as a marking spare. Thus, the ball can be marked, spoiled, roved, whatever – the only way it is getting forward is through a long, high kick to an outnumbered marking contest. It is from this situation that the rot begins.

The kick comes in; it’s a one-vs-two. The forward gets front position but is restrained by his marker just enough to not give away a free kick but allow his teammate to come across as a spare in front and take the intercept mark. The defence then quickly utilises its superior numbers to launch a counterattacking possession chain through the corridor. It is the template that this team introduced to the competition in 2015 – safe to say that it is disappointing to watch the team now be ravaged by it four years later. It gets worse however; in this situation the aerobic sweeper role from the 2018 gameplan actually makes it easier for opposition counteroffensives to break through the defensive zone and concede “cheap” goals.

The defence of the Eagles is a fine-tuned machine. It is able to comprehensively shut down opposition attacks and yet still be aggressively counteroffensive when the game is being played on its terms. That last part is the key piece – when the game is being played on its terms – because increasingly so during matches, that is no longer the case and the consequence is a major factor in the undoing of the defence of the premiership.

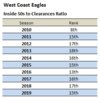

Imagine a box stretching from the centre of the ground to 40m from defensive goal one way and the width of the corridor between the wings on the other – that is the no mark zone of the West Coast defence. The entire setup of the defence as a team and its approach is geared towards preventing opposition marks from taking place in this dangerous area and forcing turnovers from intercept marks. To that end it requires the opposition to be forced into rushed decisions to get the ball forward under pressure. Additionally, the aerobic sweeper role adapted from the wing covered the lead-up space ahead of opposition targets in the corridor, ensuring that any attacking kicks coming in would be high and thus to the advantage of the Eagles’ superior marking backmen.

With the intercept mark taken in the corridor, options for counterattack were then readily available to the left, right and centre. That is the foundation behind the success of 2018.

But what happens if the intercept mark is not taken? Indeed what happens if the incoming kick bypasses the defensive trap for intercept marking entirely? That fine-tuned defensive machine becomes very vulnerable outside of its comfort zone.

So now we have an opposition possession chain counterattacking from defence with the aid of numerical supremacy from spares stationed deep behind the ball. The opposition also know to avoid that first option long kick against the Eagles in order to avoid McGovern, Barrass, Hurn, Sheppard etc. Instead they look to handball and run rather than kick. Remember 2006? The way to beat the flood was run and receive – “happy handball” as it was termed at the time. The same can be said of zones; use running chains to pull it out of shape, allowing a position where it can then be rendered useless by kicking over it. Think of it like basketball and the deployment of a compact zone being undone through the execution of play via the high-post.

When the long kick does not come, it places the entire defence on its heels. McGovern and Barrass have already pushed up and assumed the space ahead of their opponent in preparation to intercept – with the kick not coming, they are now scrambling to get back on their marks with the disadvantage of running towards goal and limited view of where the ball is. The aerobic sweeper continues to cover the lead-up space ahead of targets in the corridor, but all that does now is provide additional space for the opposition to continue the possession chain and progress into a dangerous attacking area forward of centre. When the kick does come it is deep and beyond where the defensive zone was set. In the resulting confusion to cover tall forwards, opposing non-key forwards are often able to find space behind the defence and get easy goals. All the while half the crowd boos whilst the other half are screaming out “How the %#@& did that happen?!”.

Negation of the aerobic sweeper role:

1. Aerobic sweeper is set in position covering opposition forward lead-up space.

2. Opposition creates short possession chain out of defence;

A: The defence is waiting for a long kick such as this.

B: Defenders already pushing up ahead of their opponents, positioning for the intercept opportunity.

C: The disposal instead goes to a runner in the corridor that is able to exploit the open space in front of the aerobic sweeper.

D: Players still more concerned about preventing the potential lead than arresting the movement of the ball.

2A. Conversely, if the intercept mark were to be taken in such a position, the team would be well-placed to counterattack.3. Instead the kick comes in long and bypasses the zone. Defenders are left scrambling whilst opposition forwards get behind them and gain easy goals.

With the aerobic sweeper role a liability, Masten, who had specialised himself within it to the point that he was unable to hold down any other role, was made redundant. That he was subsequently delisted at the end of the season may or may not be coincidental.

It leaves one of the catalysts behind the tactical triumph of 2018 on the scrap heap with a question mark hanging over what will be adapted as its replacement.

The Talls

The club has at its disposal the best collection of key position players in the competition. With that array of riches however comes the temptation to play too many of them, upsetting the balance of the team.

Those who are familiar with my musings will know that this is a particular theme that I have raised on numerous occasions previously, most recently at length here.

Later in this piece it shall be discussed that the biggest tactical development in the competition over the past two seasons has been the emphasis upon rebounding and attacking from defence. Such tactics favour players with pace and overlap running ability, typically not characteristics of key-position types. Turning that around, the conclusion is the more key talls that are fielded on the ground, the greater the disadvantage against the overall trend of the competition.

In 2019 this conclusion proved true for the club, especially so up forward.

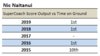

Starting with four tall forwards and two rucks in Round 1 against Brisbane, throughout the season a preference for marking advantage in attack drove the selection of the team for a negative return:

Average score differential across quarters for numbers of KPP used up forward.

Fewer numbers correlate with both greater scoring overall and in the later periods of matches.

2018 demonstrated without question that two specialist key forwards in addition to a resting ruck/forward was a platform for success – namely premiership success. It has also had the most success this season out of varying forward arrangements.

It remains to be answered why on earth anybody would deviate from it, when it is by far the best option available?

Combined, these factors resulted in the team having the following shortcomings in season 2019:

- Unable to apply pressure to opposition ball-carriers

- Unable to force opponents into making turnovers

- Unable to move the ball forward effectively when in possession

- Unable to win contests outside of stoppages

The statistics in these areas are pretty damning:

There is work that needs to be done before the club can lift up the Cup again in September.